Martian Probes

In the late 1950's, engineers at Draper developed the first martian probe using proven guidance technology from their military work. The team actually built a prototype to prove to NASA they had the chops to build a viable spacecraft system to the moon. The Mars probe never flew, but it earned Draper a spot on NASA's Apollo design team.

Key People

The MIT Instrumentation Laboratory later renamed Draper after its founder, gained its experience in inertial systems for ballistic missiles, submarines, and aircraft in WWII. In 1957 Draper made a proposal to the U.S. Air Force, for a 150 kg., unmanned probe, which would fly by Mars and take high-resolution photographs at close range. The Mars Probe was a pioneering effort by Draper to solve the problems associated with an extended space flight. Draper enlisted the aid of Avco Corp., the Reaction Motors Division of Thiokol Chemical Corp., and MIT's Lincoln Laboratory to design a vehicle that could be launched from earth into a path that would take it to Mars. En route there would be periodic navigation fixes by a star-tracker which would be used to correct inaccuracies in the probe's flight path. At Mars, the probe would take a single high-resolution photograph of about 40% of the planet's surface and then begin its return trip to earth. Upon returning, a reentry vehicle would detach itself from the rest of the probe and return to the earth's surface to be recovered at sea with its cargo of film.

Gallery

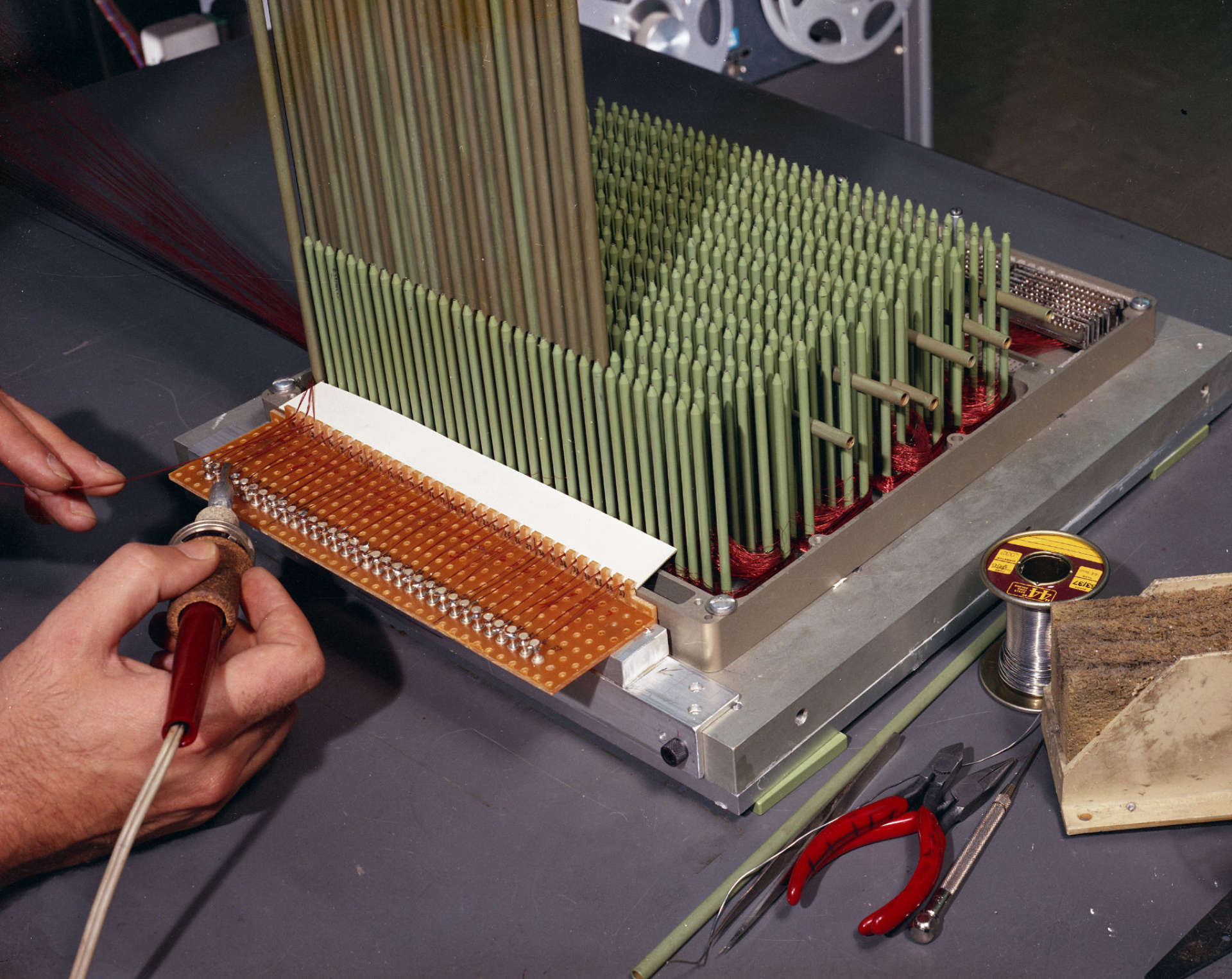

Though it received quite a lot of press attention, the project was never completed as it was quickly overshadowed by the Apollo program. Though the concept of the probe was a modest one, there were several major obstacles which had to be overcome, the most groundbreaking would be the concept of a low-power yet high accurate computer which would coordinate the functions of the probe. It used an indestructible read-only memory and served as the starting point for the development of the Apollo computer. A number of other features of the probe were also further developed during the Apollo program, but probably the probe's most significant benefit was that it fostered the team that would go on to engineer the Apollo spacecraft navigation system. When in 1961 Draper was given the job of developing Apollo's guidance and navigation, this group's presence allowed Draper to offer concrete solutions to NASA with far less development time than would have been otherwise required.